Oppenheimer: "I am Become Death", A Reading List, and More

The best of J. Robert Oppenheimer, in honor of the upcoming film.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, remains an elusive figure to the American public even as his creation looms large. In honor of the Christopher Nolan film Oppenheimer premiering, I have compiled the moments of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life that initially drew me to him two years ago as the brilliantly charismatic yet apocalyptic figure that he is.

I hope the moments below will offer you the same fascination it has to me these past two years.

The Destroyer of Worlds

1963: We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed. A few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, “Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.

A Miserable Undergrad

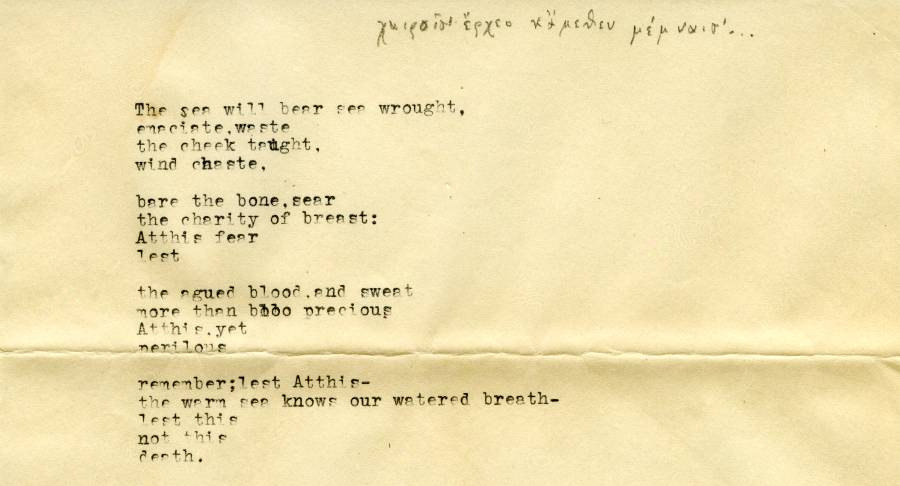

1923: Oppenheimer was a freshman at Harvard and—always prone to “baroque exaggeration”—wrote a letter to his mentor and high school teacher Herbert Smith of his time at college.

Generously, you ask what I do. Aside from the activities exposed in last week's disgusting note, I labor, and write innumerable theses, notes, poems, stories, and junk; I go to the math library] and read and to the Phil lib and divide my time between Meinherr [Bertrand] Russell and the contemplation of a most beautiful and lovely lady who is writing a thesis on Spinoza-charmingly ironic, at that, don't you think? I make stenches in three different labs, listen to Allard gossip about Racine, serve tea and talk learnedly to a few lost souls, go off for the weekend to distill the low grade energy into laughter and exhaustion, read Greek, commit faux pas, search my desk for letters, and wish I were dead. Voila.

The Trinity Test

1962: General Leslie Groves (played by Matt Damon) wrote to Oppenheimer asking why he chose the name “Trinity” for the test of the world’s first atomic bomb. Groves had assumed it was merely an inconspicuous name. Oppenheimer’s response says otherwise, though he himself cannot fully account for his choice.

I did suggest it, but not on [that] ground.... Why I chose the name is not clear, but I know what thoughts were in my mind. There is a poem of John Donne, written just before his death, which I know and love. From it a quotation:

As West and East

In all flatt Maps—and I am one—are one,

So death doth touch the Resurrection.

The poem was Donne’s “Hymne to God My God in My Sicknesse.” But the letter to Groves continues:

That still does not make a Trinity, but in another, better known devotional poem Donne opens,

‘Batter my heart, three person'd God;’

Beyond this, I have no clues whatever.

Such was Oppenheimer’s way of saying that destruction may redeem, that death might lead to resurrection, as with the death and resurrection of Christ in the Holy Trinity. Perhaps, he hoped, the death and destruction brought by the atomic bomb may end war forever and save mankind.

Oppenheimer’s Reading List

1963: Almost two decades after the atomic bombs dropped and one decade after his infamous trial, J. Robert Oppenheimer sat for an interview with The Christian Century magazine. When asked which books shaped his “vocational attitude” and “philosophy on life” he replied (in no particular order):

Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) by Charles Baudelaire

“The Waste Land” by T.S. Eliot

The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri

Śatakatraya (The Three Centuries) by Bhartrihari

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

L’Éducation Sentimentale (Sentimental Education) by Gustave Flaubert

The Collected Works of Bernhard Riemann by Bernhard Riemann

Theaetetus by Plato

Faraday’s Diary, Being the Various Philosophical Notes of Experimental Investigation made by Michael Faraday